Flavours from a banquet 139 years long

Close analysis, sharp writing, love of the game, talk about splendid moustaches - a new "biography" of Test cricket has it all

Paul Edwards

14-Feb-2016

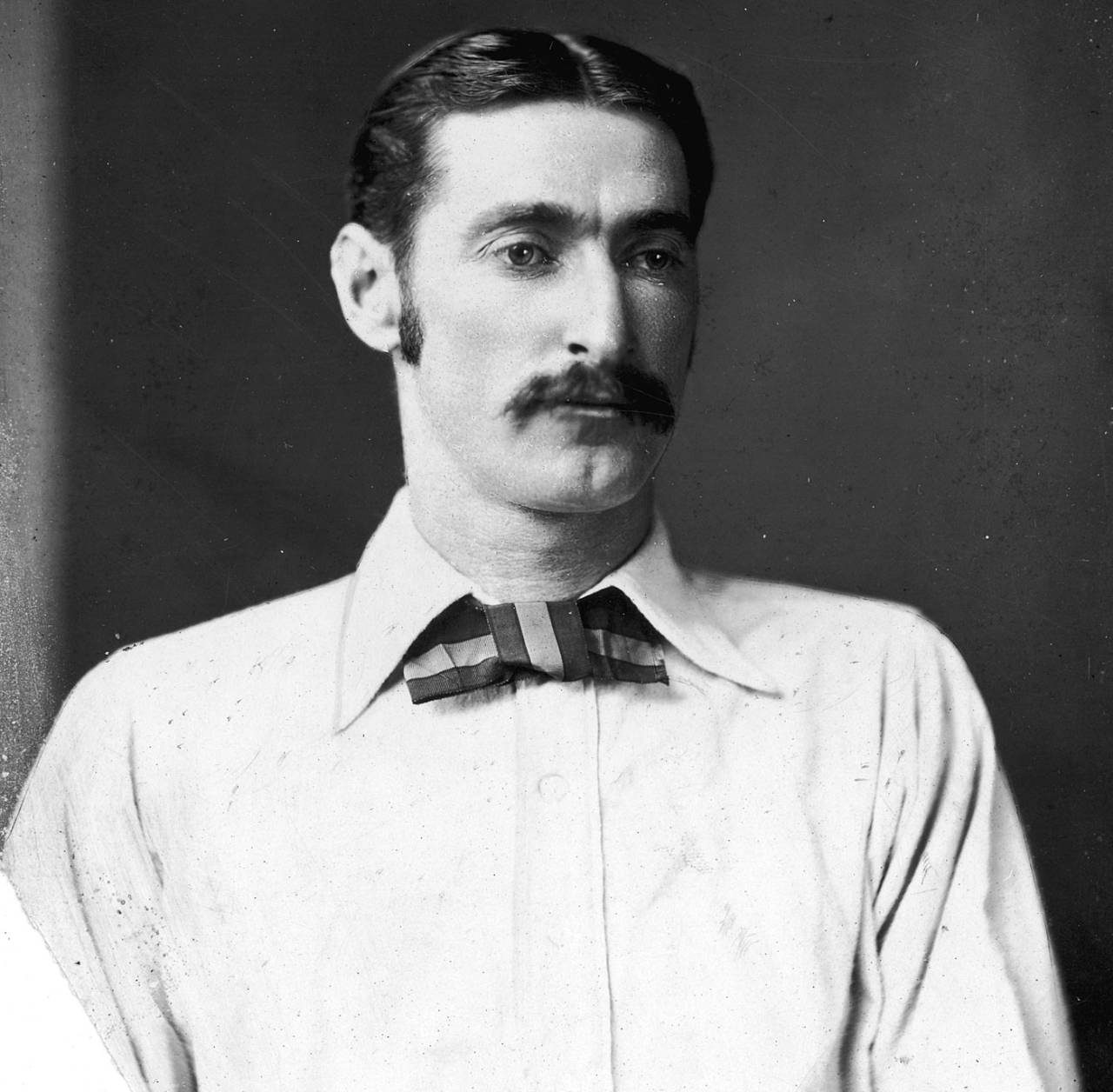

Cricket's famous moustaches get special attention in Kimber's book • Getty Images

"You have to drive the engine that has your fuel in it," said the playwright Dennis Potter. It is fine advice for any writer and the principle enshrined in the metaphor has not been lost on Jarrod Kimber*. In the seven years since his blog cricketwithballs.com cast its first irreverent eye on the cricket world, Kimber has established himself as one of the game's most sympathetic, acerbic and disrespectful observers. He is also a very fine writer with a turn of phrase some journos would maim to possess. And he has never been less than himself. Kimber does not trim his opinions or shape them so that they might fit a dominant mood. Instead, he mocks the mighty and holds cricket's absurdities up to the light, often in the one-sentence paragraphs and one-word sentences that have become two of his stylistic trademarks.

Jarrod Kimber's deep love of cricket shines brightly, particularly when he views the game with amused despair and wry anger.

Jarrod Kimber casts a cold, unsparing eye on power. Cold. Unsparing. Power.

Jarrod Kimber's close observations of a day's cricket are frequently devoted to the activities of a single player and they are often brilliant pieces of work.

In four years there were three books. One was a collection of blogs and the other two were devoted to Ashes series. Last year Death of a Gentleman, the film made by Kimber and Sam Collins, examined, among other things, the appalling governance of the ICC. It was necessary viewing for anyone interested in the game's future and in whether Test cricket even had one. One or two of cricket's megalomaniac bosses may have pondered whether Kimber took polonium in his tea.This, after all, is the author a "powerful cricket administrator" once described as "the most hated man in cricket". Another badge of honour, eh, Jarrod?

Now Kimber has written Test Cricket: The Unauthorised Biography, a title containing one of the most superfluous words in the history of publishing: unauthorised. Of course it's bloody unauthorised. The chances of Kimber currently being authorised to write anything by anyone in the ICC are around the same as the Pope asking Shane MacGowan to deliver his Urbi et Orbi address on Easter Sunday.

Hardie Grant Books

Test Cricket is typically unconventional. The current match between Australia and New Zealand is the 2201st Test to be played, although how some of the early matches came to be classified as such affords Kimber plenty of innocent amusement. It is plainly impossible to provide a full biography of Test cricket's multifaceted character in 296 pages and Kimber probably would not wish to write such a tome. Instead he has provided us with 63 chapters, some of them no longer than a couple of pages. It is a book of essays and impressions that aim to give the reader as many flavours as possible from what has been a 139-year banquet.

Now let's get the gripe out of the way, shall we? So much of this book is good and so much of it is stimulating that the little inaccuracies are particularly irritating. Why, for instance is Hedley Verity's first name spelt "Headley" three paragraphs above a sentence in which it is spelt correctly? Why did no one spot that it is Tom Cartwright, not "Tim"? And I'm not sure that anyone in Yorkshire will take too kindly to Herbert Sutcliffe's first name being reduced to "Herb". Such things may seem quibbles but a book containing so much perception and insight deserves a sharp-eyed proofreading.

Far more often, though, Kimber sends you back to the players you thought you knew. This is valuable, even when you are still not quite convinced by his assessment. For example, in his description of what I take to be the famous Beldam photograph of Victor Trumper, he writes: "His back foot is off the ground." Now I have always held the view that only Trumper's front foot is raised in that glorious image, but it is not the least of my debts to Test Cricket that Kimber caused me to spend another ten minutes examining a photograph at which I have already gazed for many hours.

There is, as we might expect from Kimber, plenty of very close analysis in the book. Moustaches get special attention. Fred Spofforth looked like he was about to twirl the end of his in the manner of a Victorian scoundrel, whereas Ted Peate's was "the sort a genial school bus driver would have. Spofforth's moustache wouldn't spit on a moustache like that." As for Richard Hadlee, the facial hair gets top billing: "That moustache. There was no way around it. It was the moustache of a villain."

Women's cricket gets far more attention than the authorities once gave to it. The opening and closing chapters about Phillip Hughes are as good as anything Kimber has written

Then there are the careers of cricketers of which one was aware but had not really considered in sufficient depth. This is Kimber's first paragraph on Aubrey Faulkner, the South African cricketer who eventually killed himself.

"Aubrey Faulkner was the sort of man that makes racists believe their own rhetoric. He was tall, broad-shouldered and looked like he was from some sort of superior sect that could, if it wanted, enslave us all."

And this is Faulkner's last Test:

"For Faulkner, the embarrassment was much worse. He had been a legend. A drop-dead gorgeous world-leading all-rounder. Now he was a man with no real balance, who had not even a hint of natural athleticism and seemed to hit the ball by accident. One of the greatest players ever would leave his last Test embarrassed."

Yet neither of those paragraphs is the best in - wouldn't you know it? - Chapter 13. This is:

"There is a dark history in cricket. There is something about the game that chews people up like no other sport. It's the Woody Allen of sports, permanently on the couch, analysing itself. Its players do the same."

Test Cricket is pleasingly rich in such stuff. It does not ignore the countries that have played only a few Tests, and even makes room for those that have played none at all. Women's cricket gets far more attention than the authorities once gave to it. The opening and closing chapters about Phillip Hughes are as good as anything Kimber has written. The book's style and organisation remind one rather of RC Robertson-Glasgow's two books, Cricket Prints and More Cricket Prints. Rather like Robertson-Glasgow, Kimber is more concerned with painting a picture than churning out statistical proofs. And like almost all good writers, he invites you to think again.

Test Cricket: The Unauthorised Biography

By Jarrod Kimber

304 pages, $35

Hardie Grant Books

By Jarrod Kimber

304 pages, $35

Hardie Grant Books

*Jarrod Kimber writes for ESPNcricinfo